Public funding for science is an essential public good. The US government spends roughly $41.7 billion funding the NIH1 and $8.2 billion funding the NSF2 every year. A large portion of that money goes to scientific grants, which are the primary funding mechanisms driving scientific research in the US. A portion of the grant money awarded to researchers is diverted to the truely strange Scientific Publishing Industry, through both open access article publishing charges (APCs) and subscription charges from “indirect costs”3. In a previous article we examined the APCs from just 9 journals (there are thousands of journals) and found the cost of publishing in those journals approached $100 million in 2021.

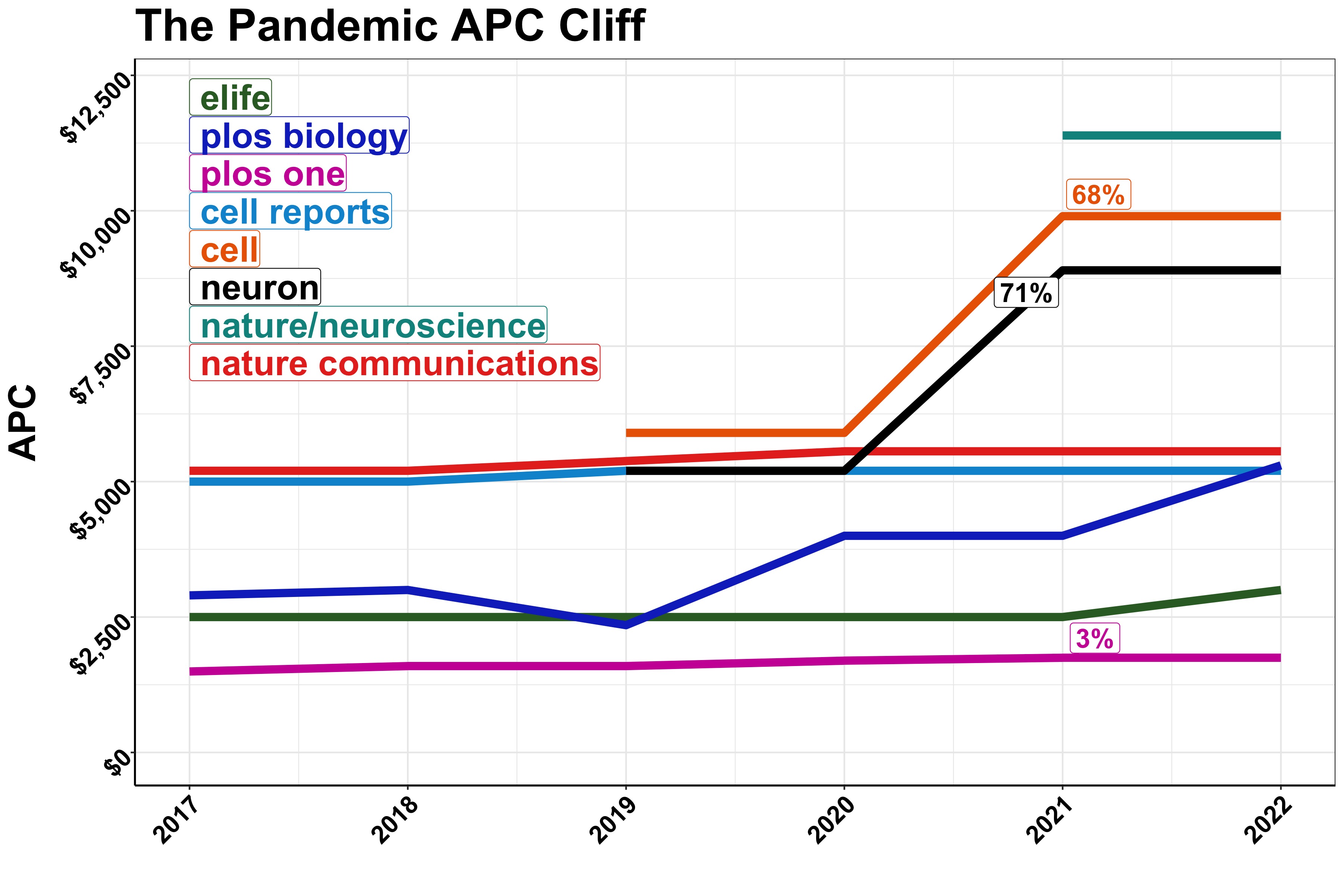

While surely not the biggest drain on scientific funding, it is worth considering whether publishers are giving us a fair deal. Recent APC price hikes from some of the biggest publishers don’t inspire confidence (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Article publishing price hikes in 2021. Plot of open access APC prices from 2017 to 2022 in the 9 journals discussed in Publishing with other people’s money. Prices were relatively stable until the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2021, when Springer Nature introduced their $11,390 APC for their competitive titles. From 2021 to 2022, Elsevier increased the APCs for its competitive Cell and Neuron titles by 68% and 71%, respectively3. Percent annotations on the graph indicate price changes from 2020 to 2021.

Who is in Charge?

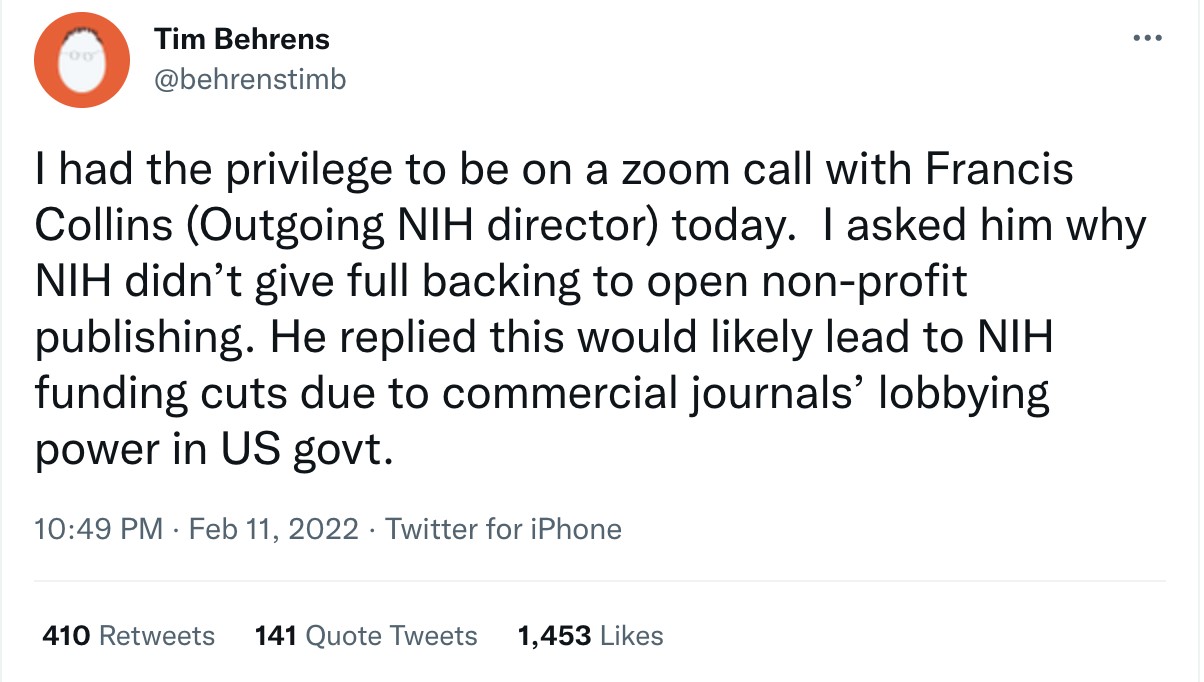

Dr. Francis Collins, star of the Human Genome Project, led the NIH for an unprecedented 13 years before stepping down in December 2021. Collins was a somewhat controversial leader, and many lined up to review his tenure. One tweet in particular stuck out to me4:

Many special interest groups lobby Members of Congress, and scientific publishing is surely no exception. However, when the outgoing Director of NIH appears to indicate that NIH policy is drawn in deference to publishers, it is worth looking closer.

The question is, who and what is Collins talking about?

The Printing & Publishing Industry Lobby

Those who lobby Members of Congress are governed by, among other rules and regulations, the Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995 and the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act of 20075. The laws around federal lobbying require certain public disclosures available through the House and Senate. Open Secrets is a self-described nonpartisan, nonprofit research group that tracks money in US politics and organizes the data from public sources. Open Secrets groups lobbying spends around “Industry Profiles”, one of which is the Printing and Publishing Industry.

In 2021, the Printing and Publishing Industry spent over $12 million lobbying Congress6.

| Client/Parent | Total (USD) | Scientific Publisher? |

|---|---|---|

| RELX Group | $2,280,000 | Yes |

| Association of American Publishers | $2,000,000 | |

| News Media Alliance | $1,746,435 | |

| News Corp | $790,000 | |

| Hallmark Cards | $430,000 | |

| MPA the Assn of Magazine Media | $419,083 | |

| Thomson Reuters | $370,000 | Yes* |

| Hearst Corp | $360,000 | |

| Wolters Kluwer | $320,000 | Yes |

| Platinum Equity | $320,000 |

Table 1: Top 10 lobbying spenders for 2021 from the Printing and Publishing Industry. The Client/Parent column indicates the group paying for lobbying, Total column is the total amount in United States Dollars (USD) spent on lobbying. The Scientific Publisher? column was added by us and indicates whether the client is involved with the scientific or academic publication industry. 3* scientific publishers are among the top 10 spenders. *While Thomson Reuters does not directly publish journals, they provide scholarly publishing analytics and proprietary citation tracking via Clarivate Web of Science, so are deeply involved and invested in the current status quo. Data courtesy of Open Secrets, see Industry Profile for Printing and Publishing (archived).

Table 1 shows the top 10 Printing and Publishing Industry lobbying clients (those who hire lobbyists) for 2021. The number 1 spender, comprising roughly 18% of the total amount spent by the industry, was RELX. RELX, previously known as Reed Elsevier, is the parent company of Elsevier, the world’s largest publisher of academic articles7.

Scientific Publishing is Big Business

For companies like RELX, science publishing is big business. In 2021, RELX reported revenue of €7,244,000,000, of which ~37%, or €2,649,000,000 came from Elsevier journals alone. RELX’s reported profit margins in 2021 were 30.5%7.

The Annual Financial Statement from RELX (archived) is a fascinating view into the Business of Science, and I’d encourage you to take a look. For example, RELX lists one of its major risks for 2022 as “levels of government and private funding provided to academic and research institutions”, indicating how dependent they are on how much governments are willing to pay for their services (page 66).

Follow the Money

RELX’s $2.3 million spent on lobbying in the US in 2021 was more than any other publishing group, including nearly 3x more than Rupert Murdoch’s behemoth News Corp (Table 1).

While few would mistakenly attribute good intentions to RELX/Elsevier, it is worth noting that they were not the only scientific publishers to spend money lobbying the federal government. In fact 3 scientific/academic publishing or analytics companies were among the top 10 spenders in 2021. Further down the list you will also find Pearson, John Wiley & Sons, and Sage Publications6.

Like pleading the fifth, there is technically nothing incriminating about spending large sums of money lobbying Congress. Indeed, many professional societies and nonprofits spend far larger sums than anyone in the publishing industry8.

What is most troubling about scientific publishing lobbying spending is how apparently cost-effective it is. For example, the 2008 NIH Public Access Policy (archived), which requires NIH funded works to be made free and available to the public (un-paywalled) within 12 months of publication, has drawn the ire of publishers since its inception. Perhaps not coincidentally, it has also been repeatedly attacked by bipartisan coalitions of publishing industry-friendly lawmakers.

Fair Copyright in Research Works Act (Conyers Bill, introduced 2009)

H.R.801, the Fair Copyright in Research Works Act9, sponsored by US Representative John Conyers (D-MI) in 2009, sought to reverse the new NIH Public Access Policy by amending copyright law. The bill would have made it illegal for federal agencies like NIH to place conditions for copyright transfer on funding agreements. Conyers was reported to have received campaign contributions from the American Intellectual Property Law Association, which strongly supported H.R.801.

RELX (then called Reed Elsevier), was also a supporter, and filed 12 Lobbying Disclosure Reports or Specific Issues for H.R.801, the most they filed for any bill in 201010. RELX was not alone– 33 unique organizations registered to lobby H.R.801. The bill was mainly opposed by libraries, universities, and professional societies, and supported by RELX and the industry group the Association of American Publishers (AAP)11.

“Conyers Bill” was referred to the Subcommittee on Courts and Competition Policy, but luckily never became law.

Research Works Act (introduced 2011)

Conyers Bill was revived by a bipartisan coalition consisting of Darrell Issa (R-CA) and cosponsor Carolyn B Maloney (D-NY) in 2011 as H.R.3699, the Research Works Act12. Why would Issa and Malone sponsor such an unpopular bill? Money was likely a motivation, as an article by Mike Taylor in The Guardian pointed to several large donations to Issa and Maloney from RELX and its top executives in 2011.

AAP again aggressively supported the bill, along with the Copyright Alliance. RELX appeared less enthusiastic for bad press this time around, and filed only 2 Lobbying Disclosure Reports or Specific Issues for H.R.3699. Lobbying activity for H.R.3699 appeared dominated by academic institutions and societies opposing the bill13.

This time, the push back from the public and academia was fierce. The Cost of Knowledge petition and editorial board resignations, among other things, likely led RELX/Elsevier to issue a statement withdrawing support for the bill. This concession was necessary to avoid an apparent open rebellion from their typically docile and affable legions of unpaid academic editors and reviewers they depend on. After RELX withdrew support, Issa and Malone followed suit and H.R.3699 was abandoned.

Abandon All Hope?

The NIH Public Access Policy was wildly popular with the public. A 2006 Harris Poll conducted while the Public Access Policy was being drafted estimated that 80% of US adults “somewhat or strongly agreed” that “research should be available for free via the internet because the research is paid for with U.S. tax dollars”14. Politicians attempting to undermine regulations as popular as the NIH Public Access Policy should always be viewed with suspicion.

However, despite industry lobbying, both attempts examined here were unsuccessful. So perhaps Collins was too pessimistic with his assessment?

The bigger lesson may be to stay vigilant. The publishing industry spends far less on lobbying than most other industries and appears to have considerably less sway. While they can push legislation under the radar, negative public responses can make a big difference, as we saw with the twice abandoned Research Works Act.

One way to check what bills the industry is interested in is to monitor the Open Secrets lobbying page for RELX or AAP. For example, here are the top 5 bills RELX is lobbying (in either the positive or negative direction) in 2022:

| Bill Number | Congress | Title |

|---|---|---|

| S.1260 | 117 | United States Innovation and Competition Act of 2021 |

| H.R.4521 | 117 | Bioeconomy Research and Development Act of 2021 |

| H.R.5844 | 117 | Open Courts Act of 2021 |

| H.R.6027 | 117 | Online Privacy Act of 2021 |

| S.2499 | 117 | SAFE DATA Act |

Any bill RELX or AAP are registered to lobby deserves some attention, and sounding the alarm early can stop bad bills in their tracks. Changing science policy takes effort and sacrifice, but it is not as difficult as many of us like to think. The Cost of Knowledge petition and the threat to stop free labor (editing and reviewing) for Elsevier journals appears to have led to RELX dropping support for the Research Works Act, and its subsequent abandonment by Issa and Maloney15.

Regular academics have more power to enact change than they think, and with the courage to use it, we could enact real change.

Further Reading

- Open Secrets is a self-described nonpartisan, nonprofit research group that tracks money in US politics and organizes the data from public sources.

- Academic publishers have become the enemies of science (archived), article by Mike Taylor in The Guardian pointed to several large donations to the bipartisan sellout team of Darrell Issa (R-CA) and Carolyn B Maloney (D-NY) from RELX and its top executives in 2011.

- The money behind academic publishing (archived), an article by Martin Hagve, covers the profits of the industry, impact factors, and Plan S.

- Lobbying Expenditures and Campaign Contributions by the Pharmaceutical and Health Product Industry in the United States, 1999-2018 A paper by Oliver Wouters covering lobbying spending in the US by the pharmaceutical industry from 1999 to 2018. Note, you can read this article for free due to the NIH Public Access Policy.

- Lobbying sways NIH grants by Sara Reardon covering target grants and the influence of patient-advocacy groups. Not necessarily a bad thing, but worth noting.

- Disease politics and medical research funding (archived) by Rachel Kahn Best, describes how advocacy shapes policy.

-

We have written about the tens of millions of dollars spent by just a handful of for-profit publishers. See Figure 3 for the APC Cliff. In our previous article, we only considered APCs for open access articles. NIH pays far more in the form of subscription costs paid by grants through “indirect costs”. Indirect costs are taken “off the top” by Universities from awarded grants and are used to fund libraries, journal subscriptions, administration costs, and other services provided to researchers by universities. See:

Knezo, Genevieve J. Indirect Costs at Academic Institutions: Background and Controversy, report, January 3, 1997; Washington D.C. (https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metacrs459/ accessed August 1, 2022), University of North Texas Libraries, UNT Digital Library, https://digital.library.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Government Documents Department. ↩︎

-

https://twitter.com/behrenstimb/status/1492269544513150977 see also archived ↩︎

-

See the 2007 Congressional Research Service Report on Lobbying (archived) ↩︎

-

For the 2021 cycle, see: https://www.opensecrets.org/federal-lobbying/industries/summary?cycle=2021&id=B01 (archived) ↩︎

-

See RELX Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RELX. The Guardian reported Elsevier’s enormous profit margins in 2017. MIT Libraries maintains a fact sheet (archived), indicating that RELX revenues were $9.8 billion in 2019, 34% of which were from Elsevier. RELX profit margins are 31.3% in 2018 and 30.5% in 2021 according to their yearly financial report (archived). ↩︎

-

For example, the American Medical Association and other health care worker societies (archived)spent over $88 million in 2021. ↩︎

-

Archived text of H.R.801, The Fair Copyright in Research Works Act, known unaffectionately as Conyers Bill. ↩︎

-

Reed Elsevier Disclosures (archived) for 2010 lobbying from Open Secrets. ↩︎

-

According to Open Secrets, 33 unique organizations (archived) registered to lobby H.R.801 in 2009-2010. AAP invited controversy for hiring public relations firms to promote their anti-open access stance. See Wikipedia for an assessment of the support/opposition. ↩︎

-

Text of the Research Works Act (archived) ↩︎

-

See the Open Secrets report on H.R.3699 (archived). Also see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Research_Works_Act#Reception ↩︎

-

Appeared in the Wall Street Journal ↩︎

-

The Cost of Knowledge petition likely led RELX to issue a statement and abandon support for the Research Works Act. The Research Work Act was abandoned by Issa and Maloney soon after Elsevier’s announcement. ↩︎