Academic publishing is an enormously profitable business. While the price tag was previously hidden behind opaque or confidential library-publisher contracts, the drive for Open Access (OA) publishing and the now-infamous article publishing charge (APC), has shown further light on the problem.

For example, Springer Nature’s prestigious neuroscience journal Nature Neuroscience recently made waves by publishing an ill-advised editorial about their $11,390 per-paper APC 1,2.

In the United States, public funding for science comes from a relatively small bucket of money doled out by agencies such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) 3 and the National Science Foundation (NSF) 4. APC payments come from this bucket of funds (as do old fashioned subscription costs) 5,6.

This misguided public relations effort 1,2 from Nature Neuroscience made us wonder, how much did scientists spend on APCs in 2021?

The Big Spend

Nature Neuroscience is a neuroscience journal published by Springer Nature. Springer Nature, a large, privately held, for-profit academic publisher, produced 3,144 journals in 2021 7. Of these journal titles, 395 were subscription only, 621 were OA, and 2,128 “hybrid” titles (containing both subscription and OA content). Elsevier, another large and controversial for-profit publisher, produced 2,873 journal titles in 2021, including 416 subscription only titles, 585 OA titles, and 1,872 hybrid titles 8.

Here, we investigated the articles published in just 3 journals each from Springer Nature and Elsevier, as well as journals from two nonprofit publishers, eLife Sciences Publications Ltd (eLife) and Public Library of Science (PLOS).

| Journal | APC (USD) | OA [total] | Type | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature | $11,390 | 163 [974] | Hybrid | Springer Nature |

| Nature Neuroscience | $11,390 | 9 [129] | Hybrid | Springer Nature |

| Nature Communications | $5,560 | 6,896 | Open | Springer Nature |

| Cell | $9,900 | 99 [488] | Hybrid | Elsevier |

| Neuron | $8,900 | 50 [316] | Hybrid | Elsevier |

| Cell Reports | $5,200 | 1,372 | Open | Elsevier |

| eLife | $3,000 | 1,995 | Open | eLife |

| PLOS One9 | $1,749 | 16,624 | Open | PLOS |

| PLOS Biology9 | $5,300 | 361 | Open | PLOS |

Table 1: APC’s for a selection of popular open and hybrid journals. The Open Access (OA) column provides the number of OA articles published in 2021. If a journal publishes both OA and subscription articles (hybrid), then the total number of articles is provided in brackets. Prices and article counts were gathered for 2021 and are our current best estimates as of January 2022. See APC Prices and the dataset for citations.

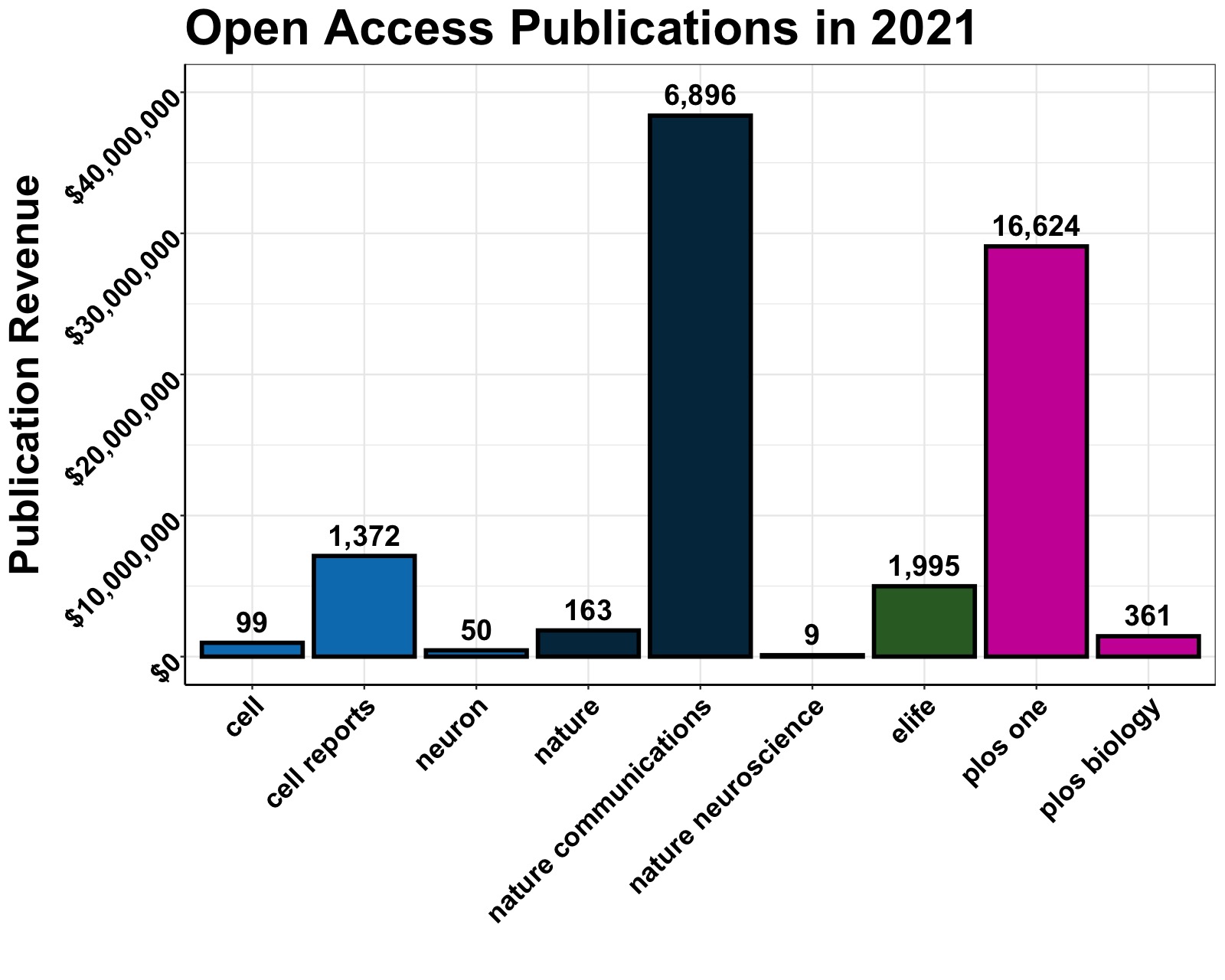

We can plot the estimated publication revenue against the number of OA articles published in each journal to get a better idea of the scale of spending on scientific publications.

Figure 1: Estimated revenue from OA articles published over the course of 2021. Data comes from 9 journals of 4 prominent life sciences publishers. The numbers over the bars represent the number of OA articles published and the height of the bar corresponds to the estimated revenue based on the published APCs multiplied by the number of OA articles published 10.

Of the 9 publications shown, Springer Nature’s middle of the road priced Nature Communications stands far above the rest. They published 6,896 OA articles in 2021 for an estimated $38 million. At the other extreme, PLOS One, from the nonprofit PLOS, published nearly 2.5x as many articles for ~20% less ($29 million).

It is important to emphasize that public money still went to Springer Nature and Elsevier for subscription-only articles published last year, but you just can’t read those articles 5.

At What Cost?

A cursory observation of the selected data in Table 1 reveals that the for-profit publishers (Springer Nature and Elsevier) charge substantially more than the nonprofits (PLOS and eLife).

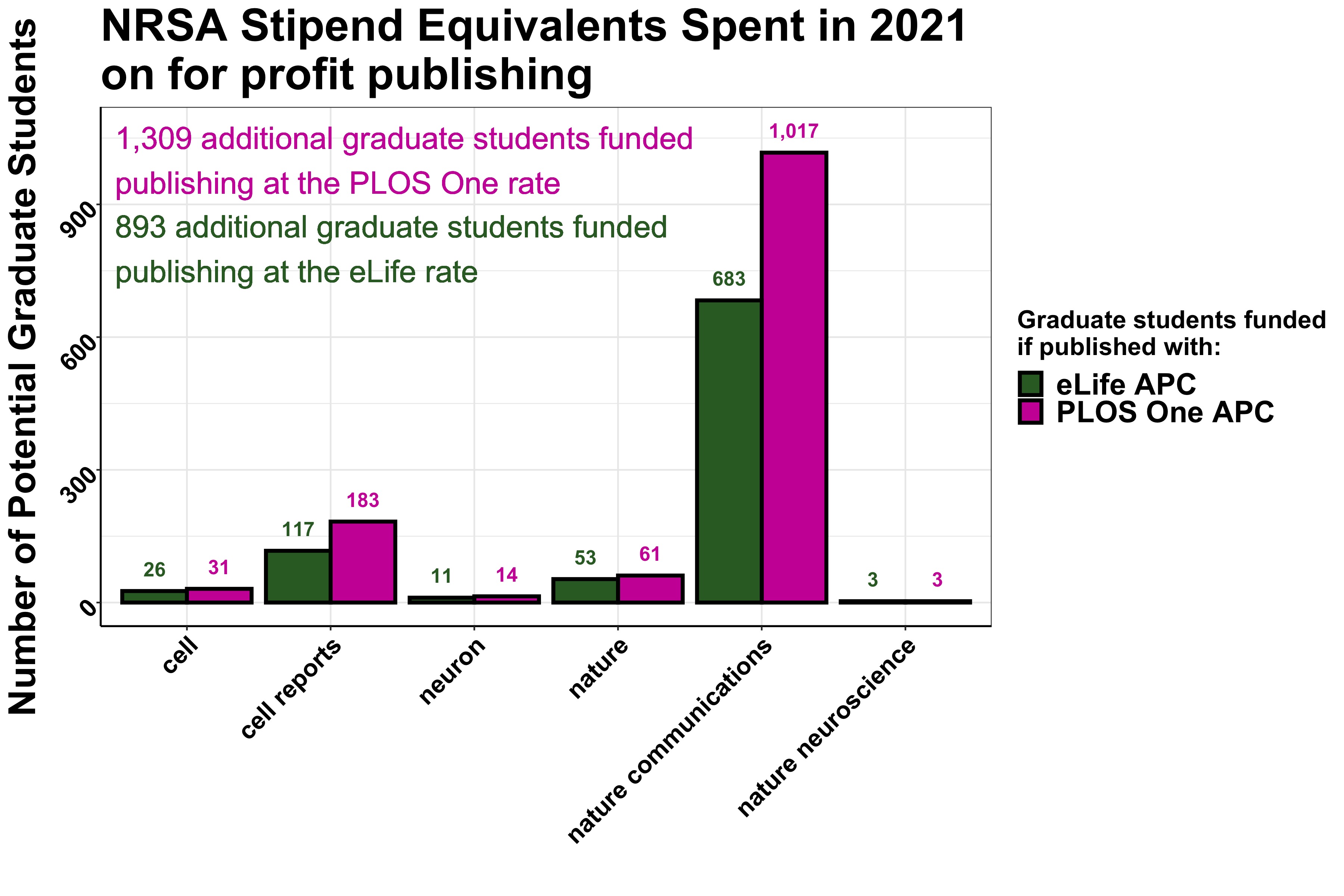

If you think in terms of the limited budget 3,4 for science, and how we fund the people who do the science, the staggering cost of all this for-profit publishing becomes clear. For example, most postdoctoral researcher and graduate student salaries in the US are funded as stipends by the NIH or NSF. One funding mechanism is the NIH National Research Service Award (NRSA) Fellowship, which funds graduate student stipends at a rate of $25,836, or about $2,153/month 11.

How many graduate-student-equivalent salaries were spent in 2021 for the privilege of publishing in this selection of for-profit journals rather than the nonprofits?

Figure 2: NRSA stipend equivalents. The number of NRSA graduate student stipends that could be funded if the same number of papers published in this selection of for-profit journals were instead published in the nonprofits eLife or PLOS One.

This plot shows the number of NRSA-level graduate student stipends that could have been funded if researchers had published in nonprofit journals rather than the for-profits, by dividing the difference in cost by the 2021 NRSA stipend 11.

$$\dfrac{(FAPC\times OA) - (NPAPC \times OA)}{Stipend}$$

Here, FAPC represents the full APC charged by the for-profit journals, NPAPC is the nonprofit APC charged by eLife or PLOS One, OA is the number of open access articles published in the given journal, and Stipend is the NRSA stipend for graduate students in 2021. Figure 2 illustrates that if all papers published in Nature Communications had instead been published in PLOS One, you could have funded over 1,000 graduate students for 1 year with the money that you saved. And that is just the savings from one of Springer Nature’s 3,144 journals.

Here are a few other comparisons:

- Publishing one paper in Nature or Nature Neuroscience costs the equivalent of 6.5 papers in PLOS One

- Publishing your work in PLOS One leaves 10K more in your research budget

- Publishing your work in eLife vs Nature Neuroscience leaves you with 8K more in your research budget

Why does cost vary?

Why do costs vary so widely? One reason may be that some journals are subsidized by academic societies, nonprofit foundations, or other funding bodies. For example, eLife is a nonprofit that receives funding from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Wellcome, Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, and the Max Planck Society. PLOS is also a US 501(c)(3) nonprofit, but doesn’t appear to receive significant support from a foundation or funding body like eLife does.

At ultra competitive journals by for-profit publishers like Nature Neuroscience, Cell, and Nature, publishers claim that sifting through the huge number of submissions consumes significant time and partly justifies the cost 12,13.

The most important thing to realize when comparing journals is that the actual scientific peer review process (which is the most important as well as the most time and expertise intensive part of publishing) should be the same for PLOS One or Nature, since the same pool of peer reviewers assess the articles from both publishers, at the same rate ($0).

If all articles are peer reviewed by the same pool of researchers (which constitutes the primary editorial “cost” for most publishers), then what drives the cost discrepancies?

From Elsevier:

We set APC prices based on the following criteria which are applied to open access articles only:

- Journal quality;

- The journal’s editorial and technical processes;

- Competitive considerations;

- Market conditions;

- Other revenue streams associated with the journal.

I think it is fair to say that “competitive considerations” and “market conditions” are likely dominating this price discrepancy.

In fact, the APC price ceiling seems to be driven by “what other people are getting away with” rather than an honest assessment of the cost:

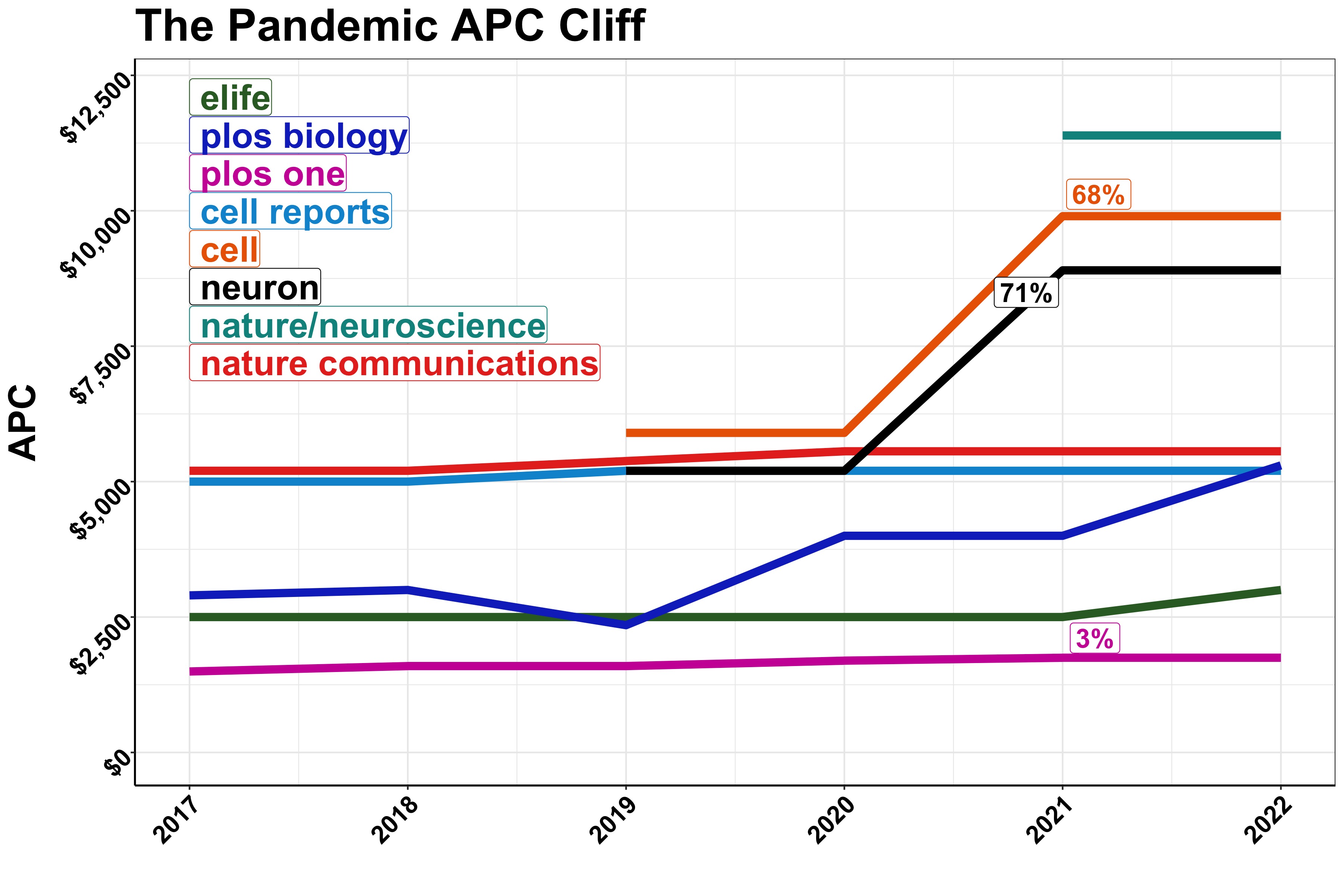

Figure 3: The APC price cliff. Plot of APC prices from 2017 to 2022 in the 9 journals discussed in this article. Prices were relatively stable until the height of the pandemic, in 2021, when Springer Nature introduced their $11,390 APC for their competitive titles. From 2021 to 2022, Elsevier increased the APCs for its competitive Cell and Neuron titles by 68% and 71%, respectively. PLOS One raised their APC 3% from 2021 to 2022.

You can see in this plot of APC prices over time for the 9 journals discussed here, prices were relatively stable from 2017-2020. In 2021 (in the midst of a global pandemic), Springer Nature announced their new APC for OA articles in their ultra competitive journals (Nature and Nature Neuroscience included), setting the price at $11,390.

It appears that around the time of Springer Nature’s announcement, Elsevier discovered significant hidden costs for the similar competitive journals Cell and Neuron, and was forced to raise APCs by 68% and 71%, respectively from 2020 to 2021.

Other people’s money

Researchers spend money on all kinds of silly things, but what is so egregious about the for-profit publishing fees is how little real value these fees buy us. Researchers are essentially paying (either directly through APCs or indirectly through library subscription costs) to add private brands to publicly funded work. Why? We generally believe that by buying, for example, the Nature brand we are really buying academic status and a perceived (likely real) increase in your and your lab’s marketability (in terms of future positions, promotions, future grants, and community status). Scientific publishers take advantage of this career incentive and the fact that, for the most part, researchers are a particularly price-insensitive group, since we are paying the fees with other people’s money.

In this light, APCs (and subscription fees) are essentially public subsidies for prestige journals. Some level of subsidy for publishers might be acceptable, but it is hard to look at Figure 3 and think we are getting a fair deal.

This is not an argument that Springer Nature, Elsevier, and other for-profit publishers shouldn’t exist– rather it is a call to start treating them like what they are: luxury brands. It is hard to argue for a public subsidy to indulge luxuries, especially when the service appears to be more expensive and less efficient than nonprofit options (Figure 1, Table 1).

Funding bodies, librarians, and researchers are on the right track by demanding that publicly funded work is made open access immediately, but are wrong in continuing to subsidize ever increasing APCs as a price. A new set of rules along the lines of Europe’s Plan S, or the NIH open access mandate 14 that required immediate open access, but set the maximum out-of-grant cost at close to cost could help address some of the runaway.

Perhaps the Nature’s and Cell’s of the world will morph into curated indexes of “Nature endorsed ‘transformative’ articles” 15. Thus reducing APC costs and maintaining the claimed value-add of selectivity 12.

Taking back scientific publishing will take time, and will face fierce resistance 16. But public funds are entrusted to us to perform science, and we should ensure that they are not wasted padding bottom lines and egos instead.

Methods

Our data came from searching publicly available data generously provided by the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed database. The majority of this data was gathered manually using PubMed’s filters, the Entrez E-utility API, or by gathering publicly available data from the publisher or journal’s respective websites. Code and data for the analysis performed here are available at: https://gitlab.com/fewmoren/someones-money/-/tree/master.

PubMed filters

When using PubMed filters or the Entrez API tools to gather publication data, We used the following parameters from the MeSH pubtype Publication Characteristics (Publication Types) to count articles from each journal:

- “Journal Article” in

publication typetags - Not

publication type“review” - Not

publication type“commentary” - Not

publication type“retraction of publication”

To group articles and sort by date, we used the “MeSH Date of Publication”, which represents when the citation was added to PubMed and may differ from the date the publication appeared in print/text.

Other publication data

Please see the dataset for specific citations for OA vs. Subscription article numbers.

APC data

We gathered APC price lists from the publisher’s websites or personal communications with colleagues who published with the journals. If you are a publisher or rersearcher who sees a discrepancy, please contact us (fewmoren at gmail).

- Elsevier APC and subscription prices

- Springer Nature Open Access APC prices

- eLife publication fees

- PLOS publication fees

For historical APC data in Figure 3, we edited and updated (using the sources above and the Wayback Machine) the excellent dataset generously provided by Walt Crawford.

-

Nature Neuroscience APC Editorial (PubMed), and on their website ↩︎

-

Indirect costs are taken “off the top” by Universities from awarded grants and are used to fund libraries, administrator salaries, and other services provided to researchers by universities. See:

Knezo, Genevieve J. Indirect Costs at Academic Institutions: Background and Controversy, report, January 3, 1997; Washington D.C.. (https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metacrs459/: accessed March 4, 2022), University of North Texas Libraries, UNT Digital Library, https://digital.library.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Government Documents Department. ↩︎

-

APC’s in the Wild, from Springer Nature argues most OA funds come “from the wild”, meaning places that are less easily tracked. However, “in the wild” sources include “coauthor pays”, “research grants”, or “personal funds”. See: Monaghan, Jessica; Lucraft, Mithu; Allin, Katie (2020): ‘APCs in the Wild’: Could Increased Monitoring and Consolidation of Funding Accelerate the Transition to Open Access?. figshare. Journal contribution. ↩︎

-

Springer Nature Journals in 2021. We downloaded the list and used the provided “sort” functions to exclude “blanks” then count the number in each category. ↩︎

-

We created this dataset by downloading the list of Active Journals, and joining it (via the ISSN column) with a CSV version of the APC price list for Open Access and Hybrid Journals. See datasets.R for the full analysis, and the dataset for raw values and citations. ↩︎

-

We used the “All Other Article” categorization for pricing ↩︎

-

Not all OA articles pay the list APC. Springer Nature and Elsevier offer certain discounts and, in some cases, waivers for OA APCs under special circumstances. We are not privy to individual payment circumstances, so keep in mind that the numbers and estimates here are just that: estimates based on our best assessment of the available information. ↩︎

-

National Research Service Award Stipend Levels for 2021. Note that most universities will supplement this salary slightly, but likely with money that also comes from the government. ↩︎

-

Springer Nature has published editorials (PubMed, Website) attempting to justify this cost (complete with estimates from the editor-in-chief of a $30K-40K per article cost), along with establishing “transformative” deals with certain libraries and universities to cover the open access charges for certain journals (Max Planck Digital Library, Springer Nature’s funding options) ↩︎

-

Note that the ultracompetitive journals are not the biggest moenymakers for the publishers. Instead, papers rejected from the most prestigious journals are often funneled to the publisher’s mid-tier journals (for example Nature Communications for Springer Nature or Cell Reports for Elsevier’s Cell Press titles). Time-weary researchers often accept with the implied promise of a faster review process due to the intra-publisher transfer. Examining this pipeline is the source for another article, but likely leads to huge profits for the publishers despite far more affordable and comparable options being available. In fact, in 2017 nearly 30% of publications in Nature Communications came from intra-publisher transfers. ↩︎

-

See the NIH open access mandate and wikipedia. This became mandatory in 2008. ↩︎

-

Someone at Springer Nature loves using “transformative” in corporate branding campaigns around open access articles. See transformative journals and transformative agreements ↩︎

-

RELX, Previously known as “Reed Elsevier” the parent company of subsidiary Elsevier, reports profit margins in excess of 40%, and spent nearly $2.4 million on lobbying in the US in 2020. That level of lobbying spending appears to be more than any other publishing group, including nearly 3x more than Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. ↩︎